Many consider the American South as the place where the struggle against Jim Crow laws, school segregation and civil rights took place. Yet, racism was just as deeply rooted in the North—and in Boston. Despite its reputation as the historic “cradle of liberty” and headquarters of the abolitionist movement, racial conflict exploded in Boston in 1974 in protest against a court order that desegregated schools by busing students in and out of previously segregated districts.

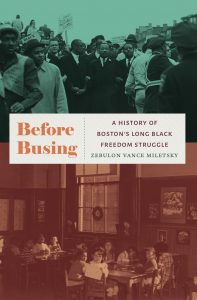

The history of Boston’s Black community is the subject of Before Busing: A History of Boston’s Long Black Freedom Struggle, by Zebulon V. Miletsky, PhD, an associate professor of Africana studies at Stony Brook University, native Bostonian and this year’s John Hope Franklin Distinguished Lecturer. On February 22, Dr. Miletsky will draw on his research chronicling 350 years of Black history in Massachusetts, culminating in 1974’s racial unrest.

The history of Boston’s Black community is the subject of Before Busing: A History of Boston’s Long Black Freedom Struggle, by Zebulon V. Miletsky, PhD, an associate professor of Africana studies at Stony Brook University, native Bostonian and this year’s John Hope Franklin Distinguished Lecturer. On February 22, Dr. Miletsky will draw on his research chronicling 350 years of Black history in Massachusetts, culminating in 1974’s racial unrest.

Here, he shares some insights on topics he will address in his upcoming John Hope Franklin Distinguished Lecture: “Before Busing: A History of Boston’s Long Black Freedom Struggle.”

The school busing crisis in Boston exposed long dormant racial conflict. How do you explain this paradox?

Boston is a city of myths. It’s the nation’s cradle of liberty. Places like Boston Latin School, the first public high school, and Harvard, America’s oldest college, take on mythic power. And there’s the myth of northern liberalism that Martin Luther King Jr. talked about.

Nineteenth-century Boston was rabidly antislavery. Yet by the early 20th century, equal rights were hotly contested. The rise of the Irish in Boston and the class wars that were playing out in Boston were major factors in this conflict. Deconstructing where they fit on a hierarchy of whiteness is important to understanding the paradox of Boston’s long Black freedom struggle.

Who spearheaded the movement to make school desegregation a reality in Boston?

Many Black people who had made their way to Boston from the South came expecting a better education, but instead got the same treatment as where they had come from.

A justice movement led by 14 black families in Boston—whose names have been hidden until recently—led to the courts, which was the only recourse available to them. Their successful lawsuit in the tradition of Brown v. Board of Education resulted in the 1974 court order to desegregate Boston’s schools and break Jim Crow’s hold over education in the North.

The upcoming Adelphi Two Museums: United We Stand program will take Black and Jewish students to Washington, D.C., to visit the African American and Holocaust museums. Do you think this program will make an impact in the fight against racism and antisemitism?

Absolutely. In the current climate, this is something we need to talk about.

What drew you to the study of Black history in Boston and Massachusetts?

Growing up in Boston and going to school after the schools were desegregated, I could still feel the pain of the past and the lingering emotional scar that required healing and justice.

I want to open the closed doors that I grew up with, and reveal the things that have long been hidden in plain sight. That’s what my book is about.

What are your current projects?

I’m pulling material from different people I’ve collaborated with for an edited volume on new directions in Boston African American history and school desegregation. There’s not much on the Boston Black freedom struggle, which is so muddied and complex. We have to figure out what happened and went wrong in Boston before figuring what’s wrong in America.

I’m also working on my next book about interracial marriage and passing in Boston and Massachusetts. There’s truth to the myth that Boston was more racially permissive in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Yet southerners used Boston as an example of interracial marriage gone wild at the time.