Why would these Adelphi students prefer to spend hours doing research?

By Ela Schwartz

Drop in on students in the labs at Adelphi or at a poster presentation, and you can’t help but pick up on the excitement. What led to the disappearance of Neandertals? What can we learn from ancient civilizations that applies to climate change? Can we lay the groundwork that could result in a drug that would benefit millions of people in the developing world?

Why would these Adelphi students prefer to spend hours doing research in the lab or the field rather than attend football games and pep rallies? Students point to professors who take them under their wings, eager to act as mentors and provide individualized guidance and support, helping students through the early stages of their research to the point where they’re ready to present at professional conferences or to publish. Another plus is small departments where students and faculty are like family and undergraduates take the spotlight. Many students reap the rewards of graduate school scholarships, fellowships and the sense of accomplishment that comes from knowing their work has added to the research in that field.

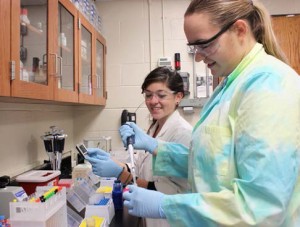

Sierra Beck and Samantha Muellers working in

Dr. Brian Stockman’s chemistry lab

Chemistry for the Greater Good

If you happen to be reading Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters, check out “Identification of proton-pump inhibitor drugs that inhibit Trichomonas vaginalis uridine nucleoside ribohydrolase.” The paper sets forth how the researchers found a compound that blocks one of the enzymes the trichomonas parasite needs to survive. The paper is credited to seven authors. The first author listed is Tara A. Shea, a senior in the Department of Chemistry, and the final name is that of Brian Stockman, Ph.D., associate professor.

Dr. Stockman explains that trichomoniasis is a sexually transmitted disease in which some strains are becoming resistant to drug therapies. The trichomonas parasite is more prevalent in developing nations but is also becoming a concern in the United States.

Dr. Stockman worked in the pharmaceutical industry for more than a decade before joining academia. He said his students’ research could lead to “a type of therapy that is of no interest to big pharma because there’s no market for it…yet. But it’s a large unmet medical need worldwide. I’m trying to teach my students that there’s a definite connection between what they do and improving the human condition, which is what I’m interested in doing now.”

Tara Shea working in

Dr. Stockman’s lab

The students work in two groups, each of which targets a different enzyme. Shea has been joined in Dr. Stockman’s lab by Sierra Beck, a junior and 2015 McDonell Summer Research Fellow, and Samantha Muellers, a sophomore.

The three students all agreed that they wouldn’t be having the same experience at a larger school, where, Shea noted, students may be slotted into a 15-minute block to work on the NMR (nuclear magnetic resonance spectrometer). “Here, I can run [results] overnight,” she said. “Everyone knows your name, even the professors I haven’t had for a class.”

Shea presented at Adelphi Research Day in 2014 and at the 2014 and 2015 American Chemical Society meetings.

“My role is to teach them how to think about the project, then stand back and take a very hands-off approach,” Dr. Stockman said. “It’s like a little Pfizer here…except the people are younger.”

Unearthing History

Brian Wygal, Ph.D., assistant professor in the Department of Anthropology, has students who have analyzed colonial artifacts at Leeds Pond or researched the disappearance of Neandertals in Europe. But most come to him intrigued by his own specialty, archaeology in Alaska.

Brian Wygal, Ph.D., and Katelynn Kelly at work in the anthropology lab.

He puts them to work in the anthropology lab, cataloging artifacts and analyzing data. In the summer they attend his archaeological field school in Alaska. And that’s when the magic happens.

“You’re excavating places people were using 12-16,000 years ago,” he said. Every student finds something, he explained, perhaps a spear point or remnants of a hearth. Artifacts are then examined and analyzed for what they can tell archaeologists about the bigger picture: what life was like among this group of people from so very long ago.

Senior Katelynn Kelly can relate to Dr. Wygal’s fascination with his chosen subject. She describes how, during her first summer at the Alaska field school, she and her fellow attendees walked through the woods looking for a site with signs of cultural activity. “I found myself surrounded by the Alaskan wilderness and prehistory, and I knew I never wanted to leave that. I was hooked.”

Archaeology is Kelly’s way of “re-creating and understanding our past…one of the greatest mysteries,” she said. Kelly researched wild bird fauna in Alaska and what these remains can tell us about early Alaskan hunters.

“Professor Wygal encouraged me 110 percent,” Kelly said. “We’re a small department with an amazing group of professors who love what they do. I couldn’t ask for more, and I know that the other students feel the same way.”

Her goal is to work in Alaskan cultural resource management, which she describes as educating the public of the significance of archaeology and maintaining and preserving sites. “With climate change, layers of the ground that used to remain frozen year-round are starting to thaw. The landscape is changing, and prehistoric evidence can be disrupted in the process. I would love to be a part of protecting it.”

Kimberly Rieger studied

anthropology in Crete.

Kimberly Rieger found her inspiration in a classroom, not the field—namely, in Dr. Wygal’s Rise of and Fall of Civilizations class, where she became fascinated with Neandertals.

According to Rieger, “I approached Dr. Wygal and said, ‘I’m really into this, what can I do?’ He said, ‘You can do some research.’ He let me go for it. His own research is important, but he’d never push it on me.

“Neandertals are seen as cavemen who weren’t smart,” she said. “But they were incredibly intelligent. I became an advocate for them, if you will.”

Rieger tested her own genome as part of her research and found she has 2.5 percent Neandertal and 3.2 percent Denisovan (a recently discovered hominid) DNA.

After thoroughly researching the arguments of whether humans have these alleles because of interbreeding or through retention through a common ancestor, Rieger found stronger evidence for the latter. In 2014 she presented her research at the meetings of the Alaska Anthropological Association and the Northeastern Anthropological Association. In Fall 2015 she will enter the Ph.D. program in evolutionary anthropology at Washington State University.

This article appeared in the Spring 2015 edition of The Catalyst, the College of Arts and Sciences newsletter.