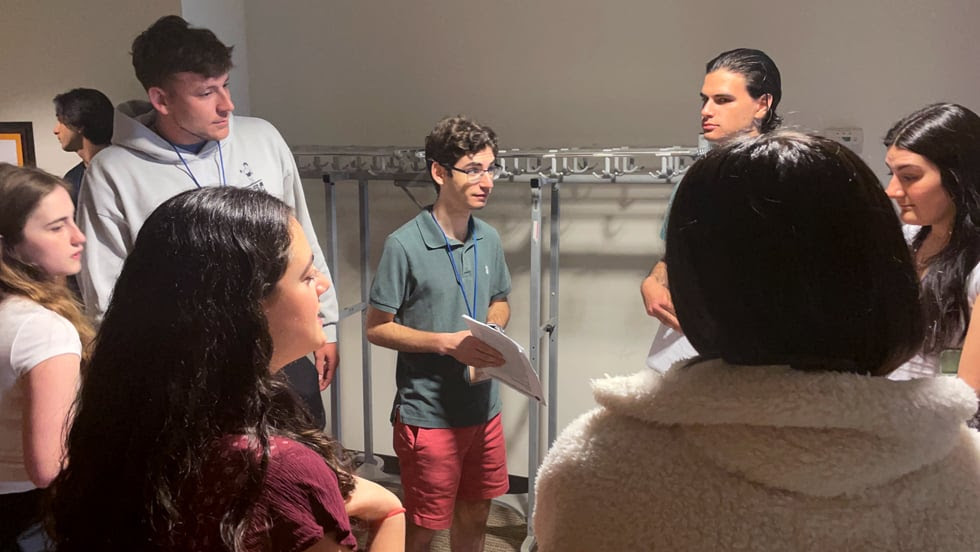

Students take on roles to learn about historical events, making for a more engaging experience in the classroom.

It’s Pennsylvania, 1757, in the midst of the Seven Years’ War, and after years of conflict, the Native American Delaware tribe and the settlers are holding a treaty council. Israel Pemberton Jr., a Pennsylvania Quaker and merchant, is responsible for negotiating with the tribe’s matriarch and rallying support for his goal of achieving peace amid Native American–Quaker tensions. Throughout the cross-cultural conversations, the matriarch, who strives for harmony, creates sacred wampum belts featuring symbols that help keep track of progress, often made of beads or belts.

But this isn’t taking place almost 300 years ago in a forest. It’s happening at the end of this semester in the class Colonial America: 1680–1763, taught by Michael LaCombe, PhD, associate professor of history. Instead of listening to a lecture, students are engaged in the Reacting to the Past role-playing game “Forest Diplomacy: Cultures in Conflict in the Pennsylvania Frontier, 1757.”

Students take on the role of fictional characters drawn from real people. The characters are part of three groups who must build alliances within their groups while also pursuing individual goals that can complicate the game. Students take on roles, negotiate, learn about other cultures and get engaged and participate.

Dr. LaCombe has played five different games in his classes over the years. “We, as historians, tend to see a group of people and try to group them together into almost a monolith,” said Dr. LaCombe. “And that’s not the way history works.”

Students Experiencing the Past

Vincent Calvagno, a history major and president of the Adelphi History Club, played the character of Pemberton. “History games require a fair bit of coalition building from students,” he said. “This is a skill that I think has utility outside the history classroom. Having the ability to pinpoint, analyze and empathize with other people’s interests is a key life skill, as is having the ability to know where to focus your alliance building.”

Cassie Tura, another history major, took on the role of Conrad Weiser, an experienced forest diplomat who served as an interpreter. She feels that the games allow students to immerse themselves in the historical period they are studying and that getting into character lets students learn the material on a deeper level.

The game’s matriarch, Jacqueline Staller, is in STEP, majoring in psychology and minoring in childhood education. As part of her role, she created eight wampum belts that feature various symbols representing various traits, concerns and goals, such as a handshake to symbolize accommodation.

“I learned a lot about our history, like how race and gender play strong roles,” she said. “Since the matriarch is a woman, I was not able to speak at the council fire meetings. I also learned about Native American culture.”

Engaging Students

Dr. LaCombe says that students may be more engaged with the class and the subject when they’re portraying characters.

“It always surprises me that people who can be very quiet in a traditional classroom setting can really come to life with these games,” he said.

Tura said participating in the game got her to “come out of my shell” as well as “make so many new friends and learn so much about my classmates on a personal level.” She also said her communication skills improved, something she said her fellow students “can take outside of the classroom and into our professional careers after college.”