What is it like to transition to civilian life after military service? What is being done on campus and by alumni to help? Find out from veterans and faculty.

As long as there has been war, there have been returning veterans, piecing their futures back together after interrupting their lives to confront hostile situations in dangerous places. Unfortunately, for many modern soldiers, the struggles don’t end when they return home.

Veterans who served in Operation Iraqi Freedom in Iraq and Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan have higher unemployment rates and are more likely to abuse drugs and alcohol than the general population. At least 22 veterans commit suicide every day due to combat stress and other issues, according to the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs

Veterans of current conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan also face a much different homecoming than veterans of previous wars. The U.S. ended conscription in 1973 and, these days, less than 1 percent of the U.S. population serves in the military (active duty, National Guard, Air National Guard and reserves), compared with more than 12 percent during World War II. Unless a relative is deployed, Americans can easily ignore overseas conflicts and most have little understanding of returning soldiers’ experiences and needs.

These issues hit close to home for the Adelphi community. Long Island has the second-highest percentage of veterans in the nation, after San Diego. The number of veterans studying at Adelphi has quadrupled in the past six years as soldiers who served in Iraq and Afghanistan take advantage of their G.I. Bill tuition benefits to earn college degrees. There are veterans among faculty and administration, including President Robert A. Scott, who served in the U.S. Navy. Helping veterans move forward is a focus for many professors and alumni from the School of Social Work, the College of Nursing and Public Health and the Gordon F. Derner Institute of Advanced Psychological Studies.

Alice Psirakis Diacosavvas ’98, a social worker who counsels combat veterans on readjustment issues at the Nassau Vet Center in Hicksville, New York, says such work is needed. “We have a responsibility as a society,” she said. “If you’re going to send someone to war, then you have to help them when they come back.”

The transition home has never been easy. It was particularly bumpy for Paul Goldman, a first-year M.S.W. student at Adelphi who served in the Marines from 1966–1970, spending a year driving an AMTRAC (amphibious tractor) at the D.M.Z. from 1966–1967. “There are so many ways you can die in war,” Goldman said at a “Conversations with Veterans” panel discussion held at Adelphi earlier this year. “The enemy shelled us constantly… There was just so much danger. You had to be hyperalert.” When he returned to the U.S., where the public’s anti-war sentiment was growing, he felt alienated. “I felt like by doing my duty I was just declared guilty,” he said. “It made me not speak about it. I didn’t tell people who I was.”

When he first returned, Goldman lived with his parents in the Long Island area, but hearing planes approaching the airport would wake him up at night.

“I thought, ‘It’s not good for me to live here,’” Goldman recalled. “I became a long-distance truck driver, because it was unsupervised and I could live at hotels. I was very nervous, so I took heavy drugs—any that was illegal that I could get I took. I drove this truck for two years. It was a liquor truck, so I could drink too.” Eventually, he decided to get his life back on track, went to college and got married, which he said, “calmed me down.” But he continued to feel jumpy. So, finally, 40 years after he returned from war, he went for mental health counseling. Now, he said, he’s excited to be starting a new chapter in his life with his social work studies.

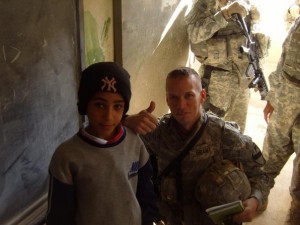

Even soldiers who feel relatively positive about what they accomplished during their service admit to feeling lost when they return home. Keith Grant, a former U.S. Army captain and current New York Army National Guardsman working toward a Master of Science in Emergency Management at Adelphi, spent two tours in Iraq in 2007 and 2009.

In 2007, in particular, Iraq was in bad shape, and as a scout patrol leader based just north of Baghdad, he led a team that patrolled Iraqi neighborhoods to keep them safe and pursued enemy leaders believed to be hiding out in certain areas.

“We had lost one soldier in the platoon just before I got there, but everyone else in the platoon with me came back together, and we had patrolled anywhere from two, three times a day for most of that year,” Grant said. “At the beginning of the year, we’d go into a village, and the folks would ask us if we could escort them to the market so they could get food. Several months later those same people would tell us, ‘Could you not come around here so much anymore? You’re backing up traffic, and we don’t really need you here.’ Those villages were safe, and we were able to come back feeling we had served a good purpose.”

After nine years on active duty, Grant decided to leave the Army in 2012 and start the next chapter of his life. Since he’d had a civilian career as a journalist before he joined the military and had left the Army with a sense of accomplishment, he was surprised to find that he felt a void in his life after he got out. That changed when he heard about the Tucson, Arizona-based Veterans Fire Corps, which trains and deploys veterans to fight wildfires, and joined the group. “I realized that what I’d needed was that next mission,” Grant said.

Now back in his hometown of Long Beach, New York, Grant is training for a career in disaster management and response and volunteers with Team Rubicon, a group of veterans that help communities clean up after disasters. Grant joined other Team Rubicon volunteers in Moore, Oklahoma, in 2013 to demolish several homes that had been damaged by a tornado, saving the homeowners the cost of hiring a demolition crew. “Being physically active and doing something positive for a community in need has such benefits for veterans as well as the community,” he said.

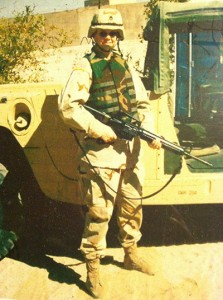

Kathleen Rickard ’14, a U.S. Army Reservist for 19 years, spent a year on active duty in Kuwait and Iraq in 2004. She worked 14-hour days supervising the loading and unloading of military vehicles and equipment from cargo ships at ports in the two countries. Even though she was stationed in a relatively safe area in Iraq, she’d hear gunshots and stray rockets at night. “I wasn’t a hero, I was just a piece of a much greater puzzle,” Rickard said. “But I can say I took pride in being as thorough as I could with my aspect of the mission, which was to ensure that the equipment was accounted for and handled properly. The military is a big machine, and if one screw falls out of this machine, it won’t work properly.”

Rickard, like Grant, went through a readjustment period when she returned to New York and her job as a sergeant in the New York City Police Department. She was edgy and forgetful and had a hard time getting back into the rhythm of being at work. “I was accustomed to getting on the bus at a certain time, eating at a certain time, doing my laundry on a certain day,” she said. “I felt rigid, and I wasn’t appreciating change.”

Rickard reacclimatized, but she remains sympathetic to the adjustment issues of her fellow veterans. After retiring from the NYPD and enrolling at the College of Nursing and Public Health, she volunteered to serve as president of the Student Veterans of America chapter at Adelphi because she wanted to be a voice for veterans. “If there were people who had questions, I wanted to be there because not everybody gets it,” she said.

“If you don’t have a family member who is a veteran or even a crusty grandfather who served in World War II, and you meet a veteran for the first time, you may think, ‘This guy’s kind of nuts,’” she said. “There’s a different way about a veteran. They come to class early, sit in the front, and if the teacher’s late, they’ve got an issue with that. They think, ‘I have a mission here: I’ve got to do well in my classes and take care of my family.’ Whereas, sometimes the younger students don’t appreciate the value of the education they’re getting.”

“I think the biggest thing that makes a lot of our transitions difficult is that there isn’t one,” said Dennis Higgins, a first-year student in the clinical psychology doctorate program at the Derner Institute, at the “Conversations with Veterans” event. Higgins served in the Army from 2001–2010, deploying to Iraq five times and Afghanistan twice.

Moore, Oklahoma following a 2013 tornado. Keith Grant worked with fellow Team Rubicon volunteers to safely take down what was left of people’s homes and to salvage keepsakes from the rubble.

“I got back from Afghanistan September 15, 2010, and November 1 I was a civilian,” he said. “I basically packed up my stuff and I was out. No real transition, so I had to do it myself.

“Coming into the military, they do an amazing job of preparing you for what’s ahead,” he observed. “They remove the attachments that civilians have and replace them with self-identification as a member of the military, whether it’s soldier, sailor, marine, airman. Then with a lot of the combat training, they sensitize you to what you need to do, and that changes you. And then going from training to actual practice changes you even more.

“But despite all of the initiatives they have to get you ready for life on the outside—teaching you how to write a résumé—it doesn’t, because they never change your self-identification. The friction I felt when I got out of the military and went back to school to finish my undergrad came from not knowing who I was anymore, because I wasn’t a soldier. I didn’t have missions, lives did not depend on what I did. It didn’t have that same sense of urgency, it didn’t have that same sense of direction.”

Misunderstandings and misinformation can make reentry into civilian life even more challenging for veterans. “The biggest misconception is that everyone who comes back from war has post-traumatic stress disorder. That’s not true,” said the Nassau Vet Center’s Diascosavvas.

In fact, experts say, only a minority of soldiers suffer from PTSD, a psychological disorder with four clusters of symptoms—re-experiencing trauma through flashbacks, feeling detached from people and activities, negative thoughts and hypervigilance.

That doesn’t mean veterans don’t have to go through a readjustment process upon their return, but the issues most of them face—perhaps psychological injuries like anxiety or depression as a result of being exposed to traumatic events or difficulties finding their place in civilian life—are usually less dramatic and threatening than what is typically covered by the media.

“Everyone who comes back from war is changed,” said Diascosavvas, who served in the U.S. Army Reserves for nine years herself, including three years on active duty at Fort Dix, New Jersey, after 9/11. “I don’t have to label that change as positive or negative; things are just going to be different. There’s this idea that, ‘I changed,’ without necessarily meaning to or wanting to. There’s a grieving and a loss that takes place with that.”

For those veterans who do struggle with PTSD, there is another set of misunderstandings to confront. “One of the biggest misconceptions is that people are able to shake it off, that it’s something that will go away with time,” said Kate Szymanski, Ph.D., an associate professor at the Derner Institute who studies trauma. “PTSD doesn’t work like that. There are neurological changes as a result of trauma, and it needs to be treated.”

Support from family and friends is insufficient to help a veteran overcome PTSD, and often, lack of awareness about the condition makes life with family difficult, she noted. “On the surface, somebody with PTSD can seem like a normal person, but internally they’re in constant turmoil,” she said.

“Their symptoms alternate, so at one point, they’re hypervigilant and irritable, then at the next point they feel detached, and at another point they have an incredible sense of being a bad person who did bad things. The family members are baffled—what’s going on, and who is this person?”

All veterans are susceptible to PTSD, whether or not they fought on the front lines during their deployment, she added. “Just the idea that your life is threatened or realizing that your friends are being killed is sufficient to traumatize an individual,” Dr. Szymanski said.

Adelphi professors and alumni who work with veterans use a variety of techniques to help struggling soldiers.

Bonnie Owens, M.S.W. ’94, counsels veterans in her private practice and directs a trauma and recovery program for military service members at the Seafield Center, an addiction treatment facility in Westhampton Beach, Long Island. Foremost in her approach is spreading the word that trauma is a biological fight, flight or freeze response that doesn’t disengage. Learning that anxiety, depression and hypervigilance can be indications of a stuck biological response rather than personal pathology gives veterans hope, she said, explaining, “Trauma-informed care changes the question from ‘What’s wrong with you?’ to ‘What happened to you?’”

Recently, Owens began leading kayaking excursions designed to help trauma sufferers reregulate their brains. Owens, who started kayaking 15 years ago, said the sport helped her get through a bout with breast cancer at age 40. “Exercise releases neurotransmitters and brain chemicals that stabilize our mood, so you’re actually at your most optimal mode for learning and healing while you’re exercising,” she said.

She takes groups out on the water and, while they’re paddling from left to right, talks them through relaxation techniques. Kayaking in pleasing surroundings typically has no negative associations for people and different varieties of kayaks can be used for paddlers in wheelchairs or those missing limbs, she noted. “The worst kind of betrayal is feeling you have no control over your own body,” Owens said. “If your body’s getting the message that it has to move [while paddling], it can’t stay engaged in fight, freeze or flight. They find something they can control.”

Brent Russell ’13, M.S.W. ’14, works with the Veterans Health Alliance of Long Island to help connect veterans to benefits and counseling. He said support from other veterans who’ve gone through the process of getting back into civilian life can be particularly helpful. He facilitates a weekly peer-to-peer veterans group in Hempstead, New York, where veterans of any conflict can share their experiences and advice.

“We listen, and then we support them as a group,” said Russell, who spent slightly less than two years in the Army after high school before receiving an honorable medical discharge because of a knee injury. “We have veterans who’ve gotten themselves together, and they come to the meeting just to support others,” he said. “Once you hear somebody has gone through the same thing, that takes the burden off your shoulders.”

“Veterans can be a hard population to reach,” he observed. “They appear for one or two appointments, then disappear again. Certain veterans want to forget. They had bad experiences—deaths of friends, seeing people getting killed, following orders that may have gone against their morals but they had to do it anyway.”

Adelphi has long welcomed veterans and military-service members to campus. The University established its School of Nursing after the United States’ entry into World War II to train members of the U.S. Cadet Nurse Corps, young women who pledged to serve as nurses for the duration of the war. After the war ended, Adelphi, a women’s college since 1912, opened its doors to men so that veterans on the G.I. Bill could also study at the school.

But G.I. Bill tuition assistance failed to keep pace with college expenses, and over the years, the veteran-student population dwindled. Then, in 2008, Congress signed a new G.I. Bill that provided greater tuition assistance, a books allowance and a housing stipend to veterans who’d served from September 11, 2001, onwards. (Dr. Scott worked with elected officials, including then-New York State Senator Hillary Rodham Clinton ’06 (Hon.) to develop the improved Post-9/11 G.I. Bill.) The current version of the G.I. Bill, coupled with an Adelphi Yellow Ribbon scholarship for veterans and a matching grant from the V.A. department, covers about 75 percent of tuition, making an Adelphi education an affordable option for veterans once again. Veterans who qualify for Federal Pell grants and New York State Tuition Assistance Program (TAP) grants may have a larger percentage of their tuition covered.

About 75 percent of Adelphi’s current veteran-students are undergraduates. Most are in their mid- to late-20s, although Adelphi also has students who are transitioning to civilian life after 20-year careers in the military. Veterans are enrolled in every school, studying all types of subjects, from history and psychology to emergency management and nursing.

The University has introduced policies and services to make Adelphi a more veteran-friendly campus (read TK ). And professors and administrators are committed to learning what returning veterans most need. Many veterans experience some culture shock when jumping into life as a full-time student after spending five or more years in the military, according to Shawn O’Riley, Ed.D., dean of University College, Adelphi’s college for adult learners.

“In the military, you have to be at a certain place at a certain time; you’re constantly checked on, and everything is formal and process-oriented,” O’Riley explained. “You come to campus and nobody checks on you; you don’t have to be anywhere at any particular time. If you’re not in class, nobody’s going to call you up and ask you where you were. Also, they may have come straight off some pretty intense service situations, and then they’re in a classroom environment with kids who don’t share that experience at all.”

While some veterans are happy to discuss their service, “we’ve found that there are many veterans who prefer not to be identified in class or on campus,” Dr. O’Riley said. “They have a strong desire to be a ‘normal civilian’ and not be called out.”

Advisers and faculty do need to treat veteran-students differently from the 18-year-olds in their classes, including regularly checking in to find out how they’re doing, the Derner Institute’s Dr. Szymanski said. “Veterans come from an environment where they’re supposed to follow orders and not ask questions, so they can be reluctant to ask for help,” she explained. “They have a lot on their plates, so helping them navigate the intricacies of academia is the least we can do.”

In spite of the challenges of serving in the military and readjusting to civilian life after war, many veterans value their service for giving them perspectives and skills they could not have obtained anywhere else. “Being in the military exposes a person to many different people, cultures and places,” Rickard said. “I learned that everyone in the world is looking for the same things—security, love, to protect their families. Change the religion or the culture, and you can still sit with just about anybody and share stories and joke around.”

“The military reflects our country as a whole,” Grant said. “It’s got people with master’s degrees and people straight out of small towns. But once you put that uniform on, whatever you did before, wherever you’re from, doesn’t matter. You’re all the same, and you’re walking together. I was able to blend right in with people from all walks of life and just loved the time that I did.”

For further information, please contact:

Todd Wilson

Strategic Communications Director

p – 516.237.8634

e – twilson@adelphi.edu