“[Perkins] insisted New York politicians visit factories and mines across the state to see the conditions themselves.”—Robert Linné, PhD, professor of education and coauthor of The New York City Triangle Factory Fire (Images of America)

Professors Frances Perkins and Annie Marion MacLean, PhD, colleagues in Adelphi College’s fledgling sociology department in the early 20th century, loom large in the history of the University—and the United States—for their unwavering pursuit of social justice.

“How remarkable,” said Robert Linné, PhD, professor of education, “that two women teaching in the same small sociology department within a young, emergent college would make such history! Dr. MacLean pioneered new sites and vision for field research and is now regarded as a mother of feminist ethnography and working-class studies. Perkins, lead architect of the New Deal and progressive labor reforms, would become one of the most impactful, yet often unacknowledged, people in our history.”

Frances Perkins: A Witness to Tragedy

Annie Marion MacLean, PhD, professor of sociology, devoted her life to improving the lives of working women.

On March 25, 1911, Adelphi sociology professor Frances Perkins was enjoying afternoon tea in a brownstone facing Washington Square Park in Manhattan when she became a witness to one of the deadliest workplace fires in U.S. history.

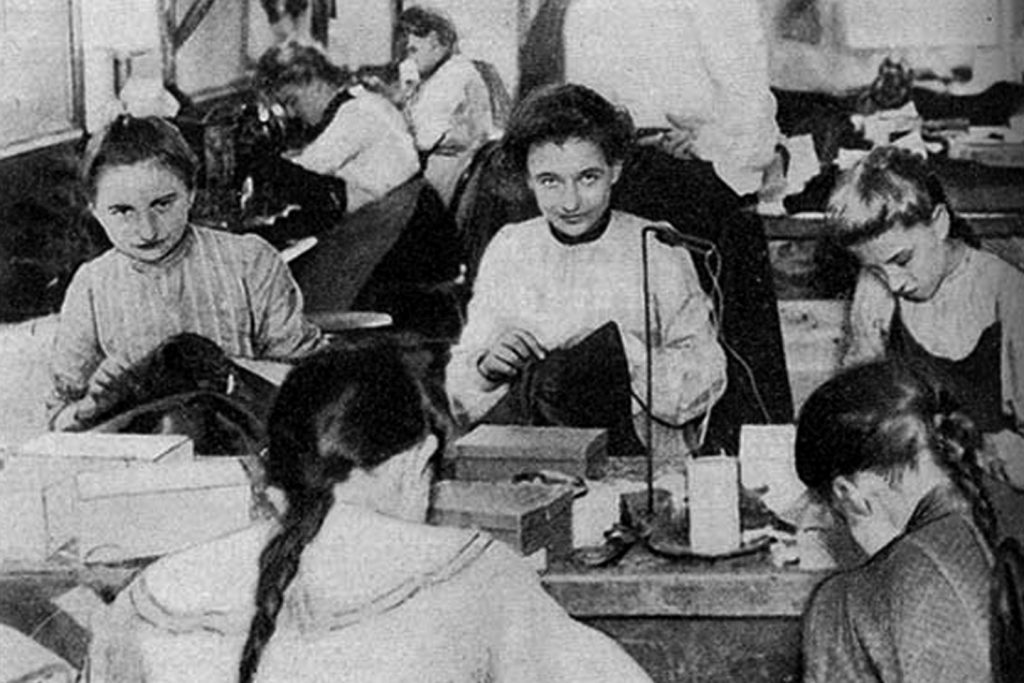

As many as 500 young Jewish and Italian girls and women worked making women’s blouses, or “shirts,” at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory, located east of Washington Square Park. The factory’s fire claimed the lives of 146 of these garment workers who were unable to escape from a building whose owners had purposefully locked stairwells and exits to prevent theft and non-sanctioned breaks. Perkins was among the crowd of horrified bystanders who watched helplessly as trapped workers leaped to their deaths.

“This moment changed Perkins’ life forever. She immediately rededicated herself to social justice.” said Dr. Linné, who coauthored The New York City Triangle Factory Fire (Images of America) and is on the board of directors of the Remember the Triangle Factory Coalition, which educates the public about the fire and is working to establish a permanent art memorial to those who lost their lives in the fire.

Perkins herself famously put it this way by saying that the day of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire “was the day the New Deal was born.”

An Impassioned Advocate

From the start of her career as a social worker and as an Adelphi professor, Perkins was an impassioned advocate for women’s rights and labor rights. After the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, she was appointed to a commission to investigate factory conditions in New York.

“Perkins determined the commission wasn’t going to be just for show,” said Dr. Linné, “She insisted New York politicians visit factories and mines across the state to see the conditions themselves. It was almost a miracle that their safety recommendations for things like sprinklers and doors that open with a push to the outside were accepted and codified into law.” With her support, the fire also helped to strengthen unions such as the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union (ILGWU), which is today part of the Union of Needletrades, Industrial and Textile Employees, or UNITE.

“The Mother of the New Deal”

Perkins’ passion and persistence ensured that Franklin Roosevelt, with whom she had worked when he was New York’s governor, appointed her to his cabinet as secretary of labor when elected president. She was the first woman presidential cabinet member in U.S. history.

“She knew she was entering a male world and played a game,” said Dr. Linné. “She purposefully dressed like a frump, so she would be considered an unthreatening aunt-like figure.”

It was in large part due to Perkins’ insistence that the New Deal included progressive reforms such as unemployment assistance, child labor laws, a minimum wage and Social Security insurance that continue to be taken for granted as part of American life.

Annie Marion MacLean, PhD: A Pioneering Sociologist

Dr. MacLean, who taught at Adelphi from 1906 to 1916, was one of the first women to pursue a career in sociology. Her cutting-edge research as a graduate student at the University of Chicago set the stage for a lifelong study of women in the workplace.

She made a name for herself with participant observations that she used to identify pressing social problems. At one point, according to Dr. Linné, she got a job as a farmworker in Oregon in order to experience first hand the conditions of working women and children.

Today, Dr. MacLean is perhaps best remembered for her groundbreaking study, Wage-Earning Women—published in 1910 while she taught at Adelphi—which employed such novel methodologies as social surveys to paint a comprehensive picture of the conditions and disparities facing working women. “Things have changed since then,” said Dr. Linné, but perhaps not enough, especially when we look at some areas such as home healthcare or farm work.

The contributions of these two Adelphi colleagues are immeasurable. As Dr. Linné remarked, “I can only imagine the conversations they must have shared together in the midst of so much change.”