When I tell others that I am training to be a psychologist, the most common response is “I could never listen to other people’s problems all day!”

Out of false modesty, I often minimize the reality of the demands we face as therapists but, if I know the person well, I’ll agree that it’s hard work and add that it requires discomforting self-reflection along with openness to the suffering of others. Still, even in these more open conversations, it is difficult for me to express what it is like to become a psychotherapist, and I doubt I’m alone in this.

The fact is, this work we do as psychotherapists is hard in many ways. We face tremendous strain when we go into a small room with another person and deliberately create conditions to encourage the expression of their most difficult emotions. We come into contact with aggression, dependency, and sexual desire, and we are expected to find ways to talk about these challenging feelings. In many cases, the pressures are unconsciously transmitted and even more draining to contain as a result. And then there’s the fact that we bring our own pasts into the consulting room. Work as a therapist, for me at least, is constantly stirring up memories of my own childhood and family, and thoughts about my own conflicts and personality. This is rewarding, but it isn’t easy!

And that’s not even getting into the topic of the settings where we work.

Freud was really onto something when he applied the term “impossible profession” to psychoanalysis. Adrienne Harris expands on this further when she writes:

[The] evolution of relational thinking places increased demands on the analyst. Always we produce and are exposed to more than we can master, know, or manage. However, you use your countertransference, it is both crucial and only ever imperfectly masterable. That mix of powerlessness, shame, and insistent demand is actually a terrible combination, a prescription for dissociation and trauma (2009, p. 6).

Writing on the demands we face as clinicians could be a source of discouragement, but, in fact, it gives me hope. At least when I’m struggling, I can know that my experiences, while deeply personal, are also shared with many others due to the nature of our work (and life itself).

Furthermore, once the nature of the demands faced are acknowledged, the necessity for self-care becomes clear, and the path to maintaining oneself can be discussed. We will break down personally, or burn out and detach as therapists, if we do not make time and mental space for our own wellness.

So, what are we to do? Vicarious trauma… compassion fatigue… burnout… self-care… These are buzzwords in the field, but do we make them more than empty speech? How can students prepare themselves for this “impossible” profession? Two questions arise: What to do to care for the self? And how to overcome the barriers that interfere with self-care?

Personal psychotherapy or psychoanalysis is one part of the self-care equation. As therapists we aim to support patients in sustaining lives outside of the consulting room, and the same can be said with regard to our own treatment. Individual psychotherapy enables us to see what we need and to seek it effectively in the world. Also, during psychotherapy one’s therapist is a source of support, and when we eventually finish treatment we take them with us internally. While “Have you talked to your therapist about it?” is a frequent supervisory comment (at least for me), bringing these issues into therapy is just the start of a larger self-care process.

Outside therapy, the self-care possibilities are endless. Kate Szymanski notes: “Self-care is doing something where you put yourself in the center. For me it’s exercise… it can be pretty much anything.” For others it may be meditation, cooking, time in nature, or travel. Time and space for thinking and feeling, and opportunities for emotional connections with partners, family, and friends are essential. Considering the self-care activities reported by current Derner students (which are listed along with this article), it seems support, emotional release, emotional processing, clearing the mind, and maintaining self-esteem are important elements of self-care.

Organized forms of peer support are also a powerful self-care tool. After graduation, many practitioners go on to join peer supervision groups. Interestingly, no formal and consistent peer supervision or peer support model has been established among Derner students. But hopefully we are making the most of the case conference.

While it may seem obvious that self-care is essential, and while making room for it is frequently emphasized, if it were easy then the burnout phenomenon in our field would not exist. So what makes it so hard to practice self-care? Dr. Kate Szymanski notes, “One fear is that if I have to take care of myself, then I’m not OK.” As therapists we must be careful not to create a split between ourselves and those we treat which leads us to apply perfectionistic standards to ourselves (such as “I don’t need help”). Additionally, Dr. Szymanski also suggests that there is a link between mythologized altruistic ideals and neglect of self-care:

It’s important to look at yourself as an equally important part of the process. In our collective consciousness putting yourself first has a bad reputation and people think it means someone is not empathetic or too self-centered. Self-care is seen as putting yourself first over patients, but that’s a myth. The reality is self-care is mindful. And if you don’t take care of yourself, how can you take care of others.

Self-care can also be difficulty given the high workloads we all carry. I know that I have found in the short-run it is easier to put my head down, but in the long run this approach cannot be sustained. Hard conversations about personal limits, or larger conversations about systemic problems of collective over-extension may be needed, and to get to the point of having these conversations may require going against ingrained personal and collective patterns. Self-care takes courage. We may wish for our needs to be magically intuited and met, but our training as therapists teaches us that maturity is being able to communicate what’s needed and negotiate for its achievement.

In my own situation, it’s been an accomplishment just to recognize being overwhelmed. The analogy of a fish in water is often used clinically to help a patient start to think about aspects of their life that are going unnoticed, and working to the point of exhaustion and ignoring my own needs has been “the water.” I know I can take pride in trudging forward and feel afraid to ask for help or acknowledge vulnerability; slowing down can be harder than staying busy. Once a supervisor (Dr. Joe Newirth) told me that if a patient is near tears but holding them back, asking them to take a deep breath will often lead to release. Slowing down and considering myself had a similar effect for me, revealing a need for self-care that I had dissociated. Therapy has been part of recognizing this, and in growing in self-care some things been helpful for me have been setting boundaries and recognizing limits, exercise (highly recommend the boxing class at the NYSC in Park Slope), and making an effort to connect more with family. The more I know myself, the more I can care for myself. I presume the same applies to others in our field, and I presume that while my experience is unique, none of us can get through Derner without facing some conflict with regard to self-care.

Does the work get easier? Dr. Michael O’Loughlin makes the interesting point that “The longer you live, the more you experience, and the more ability you develop for managing your life and responding to the lives of those you call patients… Over time, there’s more in your toolkit for managing. You develop a reference group of ideas you can draw on, and things you’ve dealt with give you new capacities.” Our work is hard, but it provides a unique opportunity for sustained emotional engagement and ongoing growth.

Finally, there is the question of where self-care fits within Derner. Should it be formally addressed in our training? I think this is worth consideration. I cannot say what form this might take, but to deny this issue is either already affecting our lives or will affect our lives would be to turn away from something true. A central aspect of our training is the cultivation of a commitment to address the elephant in the room, and perhaps self-care is one of those elephants.

References

Harris, A. (2009). You must remember this. Psychoanalytic Dialogues, 19(1), 2-21.

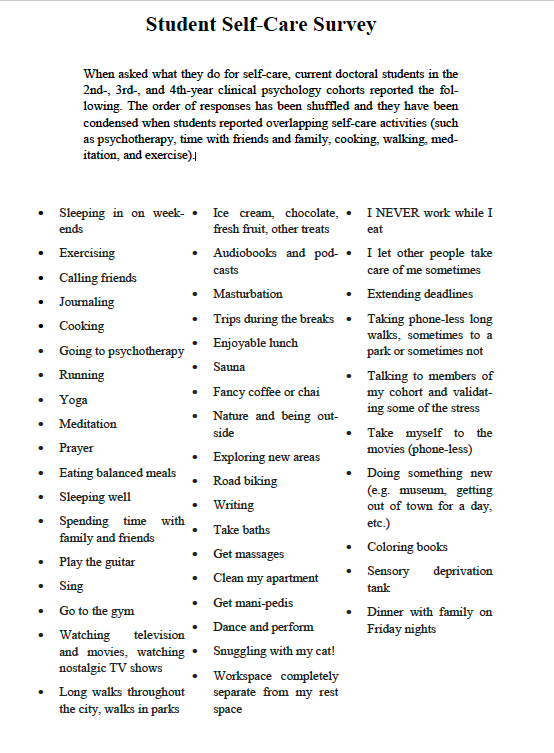

Student Self-Care Survey

When asked what they do for self-care, current doctoral students in the 2nd-, 3rd-, and 4th-year clinical psychology cohorts reported the fol-lowing. The order of responses has been shuffled and they have been condensed when students reported overlapping self-care activities (such as psychotherapy, time with friends and family, cooking, walking, med-itation, and exercise).

For further information, please contact:

Todd Wilson

Strategic Communications Director

p – 516.237.8634

e – twilson@adelphi.edu