In his recent book, Professor George Russell, Ph.D., asks "How can we begin to address the malaise of indifference to nature so widespread among our young people?"

George K. Russell, Ph.D., will retire from the Adelphi faculty at the end of this academic year. In 48 years as a Department of Biology professor, he has awakened generations of students to the glory of the natural world.

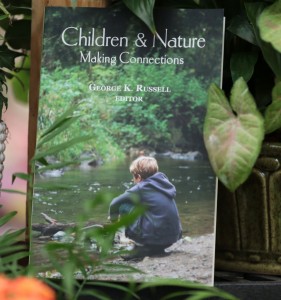

George K. Russell, Ph.D., professor of biology and author of “Children and Nature: Making Connections”

He shared his love of nature at Adelphi’s Earth Day celebration in the spring of 2014. Sayyeda Khalfan, a senior in the School of Social Work and member of the Honors College, introduced him:

“I walked into the first college biology class prepared for quizzes, exams, flash cards and memorization. I had no idea that I was about to experience a new kind of learning… Dr. Russell imparts his understanding of nature, inspiring students to engage and contemplate nature in ways we have never been taught to do. I remember learning about plant reproduction. He took our class on a field trip to the Early Learning Center, to look at the most beautiful sunflowers growing there. My fear of bees was turned into an absolute love and fascination for the creature…Dr. Russell always provides his students with a bigger picture that allows for holistic learning.”Beyond the classroom, Dr. Russell is the co-founder and longtime editor of Orion magazine, which, in his words, is dedicated to finding solutions to “the problems of our increasingly beleaguered natural environment.”

His scholarly work and his recent book—Children & Nature: Making Connections (The Myrin Institute: 2014), a compilation of essays by various authors intended to inspire readers to nurture children’s love of nature—has won him the admiration of Jane Goodall, Ph.D., the renowned primatologist. She praises Children and Nature:

“Children and Nature: Making Connections is a very important book. The fact that children are spending less and less time in nature—and some not at all—is not only a tragedy for individual children, but for the future of our species. For this contact is so important for psychological and spiritual development. When I think of my childhood I remember spring bulbs pushing up pale shoots through the dead leaves, spiders in the garden carrying tiny babies on their backs, the scent of violets and honeysuckle, and the sound of the wind rustling the leaves as I perched for hours in the branches of my beech tree. It was that magic of childhood that shaped the passion that drives me to spend my life fighting to save and protect the last wild places of the planet.”We share with you here Dr. Russell’s eloquent thoughts on the natural world and its rightful role in childhood. The text is excerpted from the introduction to his book.

Making Connections

The need and the challenge

by George K. Russell, Ph.D.

As a longtime instructor of university-level biology students, I regularly meet young people whose chief interest is the study of cellular and molecular processes, but have little acquaintance with living nature and little or no inclination to study the life sciences in a more integrated or holistic manner. There are, to be sure, numerous exceptions and our course offerings in ecology, vertebrate zoology, and animal behavior draw students with interests in field-based studies and the biology of whole organisms. I am especially heartened to find an occasional student who has spent countless hours of childhood outside in nature or one who has tended a vegetable garden and hatched butterflies. But my long experience with students concentrating in biology and a wide variety of non-majors is that many if not most have had little meaningful experience of the natural world. I am troubled by what I see as a profound disconnect between the world of nature and the interests and inclinations of so many young people, and I can foresee consequences if this matter is not taken seriously and addressed in all earnestness.

At the heart of the issue is the notion that direct personal encounter with nature, and the attendant feelings of wonder and delight, form the basis of a genuine ethos for protection of the natural environment. We will honor and preserve what we have come to love and admire, and such feelings find their source in personal experience. But what of those for whom there is little or no connection with nature? Can we expect them to participate with enthusiasm in the search for solutions to the vast array of environmental problems confronting us? And are we losing sight of the idea that each individual has the possibility of finding in the myriad wonders of nature an opportunity for self-renewal and inspiration?

At the heart of the issue is the notion that direct personal encounter with nature, and the attendant feelings of wonder and delight, form the basis of a genuine ethos for protection of the natural environment. We will honor and preserve what we have come to love and admire, and such feelings find their source in personal experience. But what of those for whom there is little or no connection with nature? Can we expect them to participate with enthusiasm in the search for solutions to the vast array of environmental problems confronting us? And are we losing sight of the idea that each individual has the possibility of finding in the myriad wonders of nature an opportunity for self-renewal and inspiration?

My own approach is to introduce, where possible, an admixture of natural history into my several courses, including definite assignments in the close observation of living nature in whatever ways I can arrange. We may not be able to visit the rainforests of Amazonia or Yosemite National Park, but we can make use of local habitats, the university campus itself, and what the ecologist David Ehrenfeld has called “the rainforests of home.” Whatever successes I have had convince me that students will take a deeper interest in the study of the living world, both inside and beyond the classroom, if they are guided to an authentic encounter with living plants and animals, natural settings, and the enchantments of life itself.

But the concern for my own students has far broader implications. My personal observations do not stand in isolation. I assembled a collection of 12 essays out of a deep concern that many young people in America have so little contact with the world of nature. A generation that spends, on average, 7 hours 38 minutes each day on some sort of screen (hand-held, video, TV, etc.) will have no time for quiet immersion in a natural setting, no time to play in nature, no time to experience the tides or the vicissitudes of the weather or the comings and goings of wild animals or the resurgence of life in the spring. Recent surveys show that many young people in this country can identify up to a hundred corporate logos but cannot name or describe even five species of songbirds, wild animals or common flowers.

A challenge stands squarely before us: How can we begin to address the malaise of indifference to nature so widespread among our young people? The implications for the future of not doing so, to my mind, are quite beyond imagining.

The task before us is immense.

The keystone of the effort is Richard Louv’s book, Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children from Nature-Deficit Disorder. Louv asserts that profound nature experience is a “spiritual necessity” for the growing child, but that the youngster who plays outdoors, like the Florida panther and the whooping crane, has become a kind of endangered species, in his words the “last child in the woods.” A fourth-grader in San Diego put the matter very succinctly: “I like to play indoors better ’cause that’s where all the electrical outlets are.” Richard Louv quotes the naturalist, Robert Michael Pyle, who asks poignantly: “What is the extinction of a condor to a child who has never seen a wren?” and Louv looks to the future with great concern, asking, “Where then will the stewards of nature come from?”

“I am especially heartened to find an occasional student who has spent countless hours of childhood outside in nature.”

I am especially heartened to find an occasional student who has spent countless hours of childhood outside in nature

Personal experience of nature lies at the very heart of the issue. Individuals who are fortunate enough as children to have had profound connections with all that nature offers—plants, animals, wild places, natural rhythms, the sky and weather, and much else—will have a firm foundation that can extend throughout their lives.

Rachel Carson is best known for her seminal work, Silent Spring, a book that helped to launch the environmental movement in the early 1970s. Carson spent her summer vacations at a cabin retreat along the coast of southeastern Maine where she found solace, repose and the inner strength to confront powerful voices not wanting to hear her messages about toxic chemicals and poisoning of the natural environment. In her 1964 essay “The Sense of Wonder” she helps the reader recapture something of lost childhood and to reflect on the sense of wonder that each child brings into life as a kind of birthright.

A child’s world is fresh and new and beautiful, full of wonder and excitement. It is our misfortune that for most of us that clear-eyed vision, that true instinct for what is beautiful and awe-inspiring, is dimmed and even lost before we reach adulthood. If I had influence with the good fairy who is supposed to preside over the christening of all children, I should ask that her gift to each child in the world be a sense of wonder so indestructible that it would last throughout life, as an unfailing antidote against the boredom and disenchantments of later years, the sterile preoccupation with things artificial, the alienation from the sources of our strength.

When asked by parents how they can teach youngsters about the natural world when they themselves know so very little about it, Carson gave the following answer:

If a child is to keep alive his inborn sense of wonder without any such gift from the fairies, he needs the companionship of at least one adult who can share it, rediscovering with him the joy, excitement and mystery of the world we live in. Parents often have a sense of inadequacy when confronted on the one hand with the eager, sensitive mind of a child and on the other with a world of complex physical nature, inhabited by a life so various and unfamiliar that it seems hopeless to reduce it to order and knowledge. In a mood of self-defeat, they exclaim, “How can I possibly teach my child about nature—why, I don’t even know one bird from another.” I sincerely believe that for the child, and for the parent seeking to guide him, it is not half so important to know as to feel. If facts are the seeds that later produce knowledge and wisdom, then the emotions and years of early childhood are the time to prepare the soil.

Carson tells us that “those who dwell among the beauties and mysteries of the earth are never alone or weary of life.” But what of those who have little or no contact with the natural world and for whom the beauties and mysteries of the earth have long since disappeared? And what of those youngsters whose lives revolve around cyberspace and technological devices and virtual images to the exclusion of anything resembling genuine nature experience? Do we not owe it to our young people to address these issues with all the determination and strength of will we can possibly bring to bear?

For further information, please contact:

Todd Wilson

Strategic Communications Director

p – 516.237.8634

e – twilson@adelphi.edu