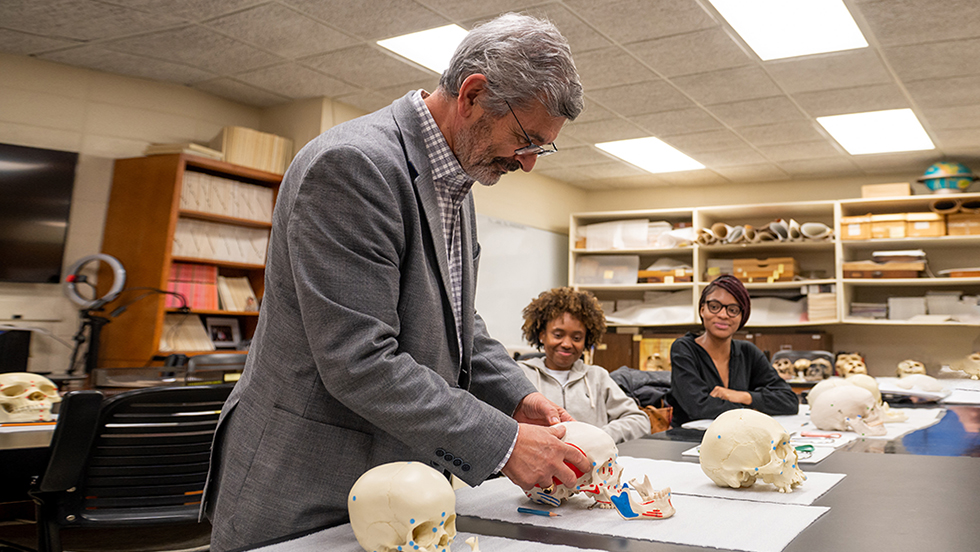

For Anagnostis Agelarakis, PhD, professor in Adelphi's history department, archaeology is an endlessly generative practice.

“Every project leads to so many others,”he said.“You keep uncovering things that invite you to go deeper, to go further, to not just stop at the surface level. And from there, you see that everything you find is connected.” In fact, the seeds of discovery planted during Dr. Agelarakis’ doctoral research in the 1980s, a study of Homo sapiens skeletal remains from the Shanidar Cave in Iraq, have continued to bear valuable fruit throughout the past several decades. Most recently, several Shanidar samples he contributed to a new project analyzing genomic data from the Southern Arc—a region bridging Southeastern Europe with Western Asia, often referred to as the “cradle of Western civilization”—proved to be the oldest out of 727 total samples spanning the past 11,000 years, providing the research team with a vital analytic foundation.

Research by Dr. Agelarakis has been widely published in scholarly journals and covered by news media throughout the world.

Led by Iosif Lazaridis, PhD, and David Reich, PhD, at Harvard University, the project was a cross-disciplinary initiative dedicated to developing the first-ever comprehensive archaeogenetic history of the Southern Arc during the Chalcolithic and Bronze Ages, dating back about 7,000 to 3,000 years. Along with more than 200 co-authors from around the globe, Drs. Lazaridis and Reich turned their findings into a trio of studies published in Science in August 2022: “The genetic history of the Southern Arc: A bridge between West Asia and Europe,”1 “A genetic probe into the ancient and medieval history of Southern Europe and West Asia”2 and “Ancient DNA from Mesopotamia suggests distinct Pre-Pottery and Pottery Neolithic migrations into Anatolia.”3 The research used a data set of unprecedented scope and size to close “major gaps in sampling in time, space and cultural context” (“The genetic history of the Southern Arc”), in the process decoding some long-standing mysteries about migration patterns, cultural diffusion and linguistic evolution among early Indo-European peoples.

Dr. Agelarakis’ Shanidar Cave sample, which dates back to the ninth millennium B.C., established a prehistoric baseline for project researchers working on later periods. Armed with information about Shanidarians’ age ranges, genders, diets, anatomy, travel patterns and survival ratios, they were able to identify connections between different groups that traversed the Southern Arc, as well as the cultural practices, skills and technologies they brought with them. According to Dr. Agelarakis, the project’s novelty cannot be overstated. “This is something I’m excited to tell my grandchildren about, how we’re able to complete a massive worldwide project that relies solely on ancient genomic samples,” he noted. “We’re the first to be able to substantiate these kinds of conclusions through molecular tracking.”

The project also lays important groundwork for other research. A recent study Dr. Agelarakis co-authored with another team, “Ancient DNA reveals admixture history and endogamy in the prehistoric Aegean” (Nature, Ecology & Evolution, 2023), builds on work completed by the Lazaridis-Reich project to illuminate connectedness in an entirely different region. In analyzing the flow of genetic signatures in Crete, the Greek mainland and the Aegean Islands between the seventh and first millennia B.C., the authors were able to confirm the biological dimensions of certain cultural transitions that had never before been mapped. Ultimately, they write, “Our results highlight the potential of archaeogenomic approaches in the Aegean for unraveling the interplay of genetic admixture, marital and other cultural practices.”

While Dr. Agelarakis looks forward to continuing his work on the Shanidarian samples, he is most excited about sharing the broader lessons of archaeogenetics with his students. “In some ways, these perspectives appear to be new, but really they’re just strengthening what we’ve been saying all along, that we are all siblings,” he explains. “Genetically speaking, our differences are minuscule; it’s only in our upbringing and our education that we create difference. We all began as hunters and gatherers in prehistoric times. I always tell my students that we have to use this data to fulfill our responsibility as custodians to the Earth—that we have to look to our common past in order to ensure a common future.”

1 Agelarakis, Anagnostis, et al. “The genetic history of the Southern Arc: A bridge between West Asia and Europe.” Science, vol. 377, Iss. 6609, 26 August 2022.

2 Agelarakis, Anagnostis, et al. “A genetic probe into the ancient and medieval history of Southern Europe and West Asia.” Science, vol. 377, iss. 6609, 25 August 2022, pp. 940-951.

3 Agelarakis, Anagnostis, et al. “Ancient DNA from Mesopotamia suggests distinct Pre-Pottery and Pottery Neolithic migrations into Anatolia.” Science, vol. 377, iss. 6609, 25 August 2022, pp. 982-987.

4 Agelarakis, Anagnostis, et al. “Ancient DNA reveals admixture history and endogamy in the prehistoric Aegean.” Nature Ecology & Evolution, vol. 7, 2023, pp. 290-303.